Frequently Asked Questions

History of Handchimes

EDITOR: The Editor determined to include information from various sources without comment. Absence of information from a manufacturer is due to non-response.The information has been included as it was received.

Readers may contact the individuals for more details.

McGowan Nance Malmark Shulmerich Patents Suzuki Sidenotes

Monica McGowan contributed this in December of 1996:

I have taught some classes on handchimes at Area VII Festivals. I attended a Handbell/Handchime workshop under Dr. Paul Rosene at Illinois State University and got a lot of information from him about the development of handchimes. I am sending you the text of what I have from my class notes as well as other research I did. If you need additional information, I would suggest you get a copy of "Overtones 1955-1986" from AGEHR

(1-800-878-5459). It's got LOTS of additional information, too."Origin and Evolution of Chime Instruments"

The first chime instruments can be traced back to Southeast Asia and some parts of China thousands of years ago. This hand-held split tube instrument was made from bamboo using the natural membrane, which resulted in a stopped tube effect. The sound of these early instruments was created by hitting the bamboo against a stationary object. Later a method was devised of holding the bamboo tube and striking it with a stick. In 1894, Edward Gerry was granted a patent for a tubular resonator. It was made of metal with a movable plug: the first use of the "stopped pipe effect."

During the late 1800's, John Deagan visited Southeast Asia where he saw the early "bamboo instruments." He took the idea with him and in 1900, he patented the first slotted metal tube, which had a tuned tine and a fixed plug -- combining and improving the designs already in existence: the split tube of the people of Southeast Asia and the fixed plug, the invention of Edward Gerry.

In 1910, William Bartholomae patented a toy that claimed no musical significance, but used an external, attached device that struck the tube to make it sound. This was the first clapper mechanism.

In 1939, Earl Sanders was granted a patent involving a tube that was slotted at both ends. Although this slotted idea was not successful, the most significant contribution of his patent changed the slotted tube from round to square. This was to play a very important role in what we have seen develop as today's chime instruments.

In 1977, an English handchime was developed by Toby Harris Smith and was described in David Sawyer's article "Vibrations" published by Cambridge University Press. This instrument used an external "spring metal ringer." However, there was an inherent flaw in the design and Mr. Smith was unable to find a workable solution to the problem and was eventually forced into bankruptcy. The handchime was made in England and distributed by

Schulmerich Carillons in the United States. Mr. David Ward, a therapist in England, used the handchimes in his music classes and in rehabilitative therapy sessions. He felt that the handchime would be a very useful addition in therapy sessions and contacted Dr. Paul Rosene, his friend in the United States. Dr. Rosene toyed with the idea of the "handchime" and consulted with Jacob Malta at Malmark, Inc.In 1981, they started experimenting with different designs, using rounded and squared tubes, using different combinations of aluminum and tin and developing a way to attach a clapper mechanism, similar to ones used in the Malmark handbells. In 1982, Jacob Malta introduced the Choirchime (R): they had found the right combination of metals to produce a "pure" tone, based on the principals of the tuning fork with an external clapper mechanism. "The sound of the Choirchime (R) is mellow, peaceful and gentle;" "a heavenly sound." There have been some slight modifications in the original design and the Choirchime (R) is marketed in nearly its original form today by Malmark, Inc.

Malmark, Inc.November 24, 2003

Mr. Jacques Kearns

2448 Apricot Lane

Augusta, GA 30904

Dear Jacques:This is in reply to your request for information on the history of the handchime. It includes how and why Malmark decided to design and manufacture its own.

In 1980, Nigel Bullen brought with him, on a visit to Malmark, two handchimes made by a Toby Heriz-Smith from a design by David Sawyer under some kind of arrangement. Nigel's concern was that the handchime was cutting his handbell sales potential, and he was hoping Malmark would manufacture an equivalent handchime. Our conclusion was that the handchimes he'd brought were more in the nature of a musical toy than an instrument, and that Malmark preferred not to get involved because we found the tonal quality weak and inconsistent while, at the same time, the clapper design had many shortcomings.

A year later, I heard that Heriz-Smith had contracted with Schulmerich to distribute his handchime in the U.S. This convinced me that I had to design a better handchime in order to meet the threat to our ability to grow our bell business.

I remembered that a J. C. Deagan had done considerable work on slotted tubes in efforts to duplicate the sound of bells in the early 1900's. It turned out that his work was very helpful.

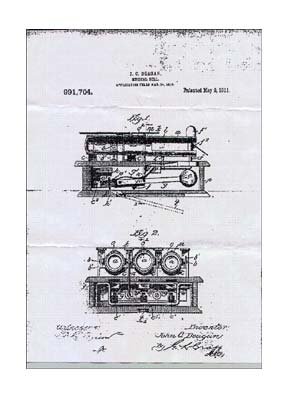

Deagan's patents cover the features of a slotted round metal tube of both the open end and closed end types with a coupled clapper assembly included in one of them. His patent numbers are: #734,676 (July 28, 1903), #818,874 (April 14, 1906) and #991,704 (May 9, 1911).

E.V. Sanders' Patent #2,153,725, issued 11 April 1939, includes coverage on the design of a metal tube of square shape.

In the early or mid-1970"s, a Roger Ames re-discovered, quite by accident, the musical qualities of a slotted square tube. His employer, Riverbank Laboratories, attempted to procure a patent on it but in light of Deagan and Sanders were not successful. This was because Ames’ "'discovery" was neither novel nor nonobvious and was already well known in the state of the art. These same facts would, therefore, apply to the English handchime which could not be protected by patent either.

We proceeded with researching the sound quality of tubes of various metals and alloys and found that stainless steel produced the richest and strongest musical tones. However, because of its being so difficult to fabricate (and, more so, expensive), we chose the next best and settled for aluminum with its rich, mellow tones and its ease of fabrication. We attached a form of our well-proven handbell clapper, and, on the inside, defined the length of the tuned air columns with adjustable friction-held plastic plugs. We increased the width of the tuning slots in the ends of the tubes and achieved a substantial increase in sound volume.

It is history that Malmark introduced its American handchime under the name CHOIRCHIMES in 1982, followed by the Suzuki version in 1986 and, more recently, the Schulmerich version, both of which, except for tube profile, duplicate the Choirchime in almost every detail.

Sincerely,

MALMARK, INC.

(signed)

President

JHM/Ims

E-Mail to Jack Kearns

November 4, 2003Dear Jack,

Thank you for your e-mail of October 25, 2003 requesting information about our development of handchimes.

You might want to look at David Sawyer’s book entitled: “VIBRATIONS, Making Unorthodox Musical Instruments” by the Cambridge University Press. Note his (pages 24 and 25) METAL BONCA and BAMBOO BONCA (pages 22 and 23).

I believe Toby Heriz-Smith produced square steel tubular chimes in the United Kingdom sometime in the late 1970’s to early 1980’s. I believe Mr. Heriz-Smith trademarked and perhaps even copyrighted the name: HANDCHIME.

Without checking the records, Schulmerich imported and sold these chimes sometime in the early to mid 1980’s. We are not aware if they are still being produced today.

In 1998 Schulmerich introduced its MelodyChime® Instrument, which is ergonomically designed utilizing octagonal aluminum tubes designed by Schulmerich. Subsequently, for the sustain of the upper 5th octave chimes our engineers developed the solid chime. More specifics are on our web page, www.schulmerichbells.com.

I trust this will assist you in developing the page for the History of Handchimes.

Regards,

(signed)

Bern E. Deichmann

President & CEO

Susan Nance provides this history on handchimes, incorporated 8/2006:Thousands of years ago, workers harvesting bamboo in South East Asia accidentally cut notches in the stalk. As stalks fell, they struck another object and produced a pitched musical sound. As other stalks were notched and struck, other pitches sounded using different lengths of joints and changing the length of the vertical notch. [i]

In 1894, Edward Gerry, inspired by the split tube, patented a tubular resonator made of metal with a movable plug – a stopped pipe effect.[ii] Also during the late 1800’s, John Deagan (1853 – 1934) visited South East Asia and saw bamboo instruments. Famous for his contributions to the field of mallet percussion, Deagan created instruments including the xylophone, aluminum organ chimes, and “roundtop” orchestra bells (in which the top of the bell is a convex shape and the full tone of the bell can be produced when struck at any angle). In 1910, Deagan persuaded the American Federation of Musicians to adopt A=440 as the standard universal pitch for orchestras and bands. In 1900 he patented a slotted metal tube which had a tuned tine and a fixed plug which combined and improved on the split tube of South East Asia and the fixed tube of Edward Gerry.[iii]

Bamboo was also used in instruments created by Harry Partch (1901 – 1974), an instrument maker and composer. Partch designed bamboo mirambas, or Boos, that were tuned with a single slot and clamped with a jubilee clip to prevent splitting. David Sawyer of Exeter developed a slotted metal tube struck with a beater that he called Metal Boncas. Sawyer's instrument had a longer decay time and did not split when struck as the Boos did. David Ward, the director of the Music Advisory Service of the Disabled Living Foundation, observed children living with cerebral palsy playing with the metal boncas and suggested to Sawyer that a chime bar with a beater attached would improve the children’s chances of making music.[iv] Sawyer designed an English handchime with square steel tubes using an external spring metal ringer, developed by Toby Heriz-Smith.[v] The inherent flaws in the design forced Smith into bankruptcy. In an email to Jack Kearns dated 11.4.03, Bern Diechmann, the President and CEO of Schulermich, indicated that the company imported the chimes without checking the records and sold the product through the mid 1980’s.[vi]

In response to Schulmerich’s decision to distribute the handchimes, Malmark designed a different handchime to continue growing in the bell business. In a letter from Jake Malta to Jack Kearns, Malta referred to John Deagan’s work on slotted tubes with open and closed ends and one with a coupled clapper assembly copyrighted between 1903 and 1911.[vii] Malmark researched the sound quality of various metals and alloys and found stainless steel to produce the richest and strongest musical tone. Unfortunately, stainless steel was very expensive and difficult to fabricate. The second best and least expensive alternative was aluminum which produced rich, mellow tones, and was easy to fabricate. A version of the handbell clapper was added, and in 1982 Malmark introduced Choirchimes. Suzuki’s version followed in 1986.

In 1998, Schulmerich introduced the MelodyChime. Schulmerich’s handchime is different from Malmark’s in its shape and ringing mechanism. The ringing mechanism is like the handle yoke, assembly and the tension control is much more stable and flexible.

[i] C.H.I.M.E. Spring 1998

[ii] www.knology.net/~jkearns/handchimehistory.htm [Ed note: this refers to the original location of this file and appears above]

[iii] www.knology.net/~jkearns/handchimehistory.htm [Ed note: this refers to the original location of this file and appears above]

[iv] C.H.I.M.E. Spring 1998

[v] Sawyer, David. 1998. Resources of Music, Cambridge University Press "Vibrations: Making Unorthodox Instruments", Cambridge.

[vi] www.knology.net/~jkearns/handchimehistory.htm [Ed note: this refers to the original location of this file and appears above]

[vii] www.knology.net/~jkearns/handchimehistory.htm [Ed note: this refers to the original location of this file and appears above]

If you have questions you feel should be included in this FAQ, contact . It will be helpful if you will state the question similar to those above, and if possible, give a short, definitive statement to answer the question. The editor will review your question and answer, consider whether to include the question, and amend as deemed necessary.

Contact for information about this page.